photo by Alex Lear

ALABAMA

1.

it is late in december 1998, the weather is uncharacteristically warm. there is much that is wrong. an old man has killed himself.

if he had been an airplane and fell from the sky, the forensic engineers might have diagnosed: metal fatigue—the quality of structural breakdown when the weariness caused by the ravages of time destroy an object’s physical ability to bear the weight of existence. but this fellow was not a passenger jet. he was just a chestnut colored, elderly african american whom everyone said looked remarkably good for his age.

his eyesight was fit enough—without glasses he could drive day or night. and he would step two flights of steps rather than wait on a slow elevator. he was sensible about his diet and walked two miles every morning to keep his weight down. plus, any day of the week, he could out bowl his son. no, his age was not a problem.

so what was so disastrous in his life that the permanent solution of suicide was the action of choice to deal with whatever temporary problem he was confronting?

we are not sure what exactly was wrong, but we do know that when he resolved to end it, he was watching television. got up and said something to his wife, who was in the kitchen. shortly thereafter went into his back yard with a gun in his hand—no one in the house saw him go outside. but what if they had? could they have stopped him? probably not. at best they may have been able to momentarily postpone the inevitable, but eventually life turns cold. or we are deluged with the dreariness of chilly rains. and we die.

what did the slow moving man think as he descended the steps into the back yard? indeed, did he think, or was his mind blank with certainty?

his body died there, but was he already dead in spirit? does it matter what happens to the body, once the spirit has been broken? this is a story about death.

2.

i have often thought about those stark black and white photographs of lynching scenes. we know what happened to the lynchee, but what happened to all the lynchers? the ones standing around. some smiling into an unhidden camera—look, you can see that these people know that a photograph is documenting them. a number of them are looking at the camera full on, challenging the lens to capture something human in the grisly scene. a significant number are children, young boys and girls, leering.

i have heard stories of whites who were repulsed by those death scenes. those who were changed forever by witnessing a lynching, hearing about a lynching, backing away from their parents come back home chatting about the nigger who got what he deserved. ok. but what i want to know is what happened to the lynchers who did not back away. those who took in the murder scene as acceptable. later on in life, how did they raise their children? do they have flashbacks of lynchings—occasionally? often? never?

does watching a man or woman die a violent death diminish the person who enjoys the spectacle? can one revel in the fascinating flame of a human on fire and afterwards remain emotionally balanced? and what about memory, does the extreme violence of mob murder involuntarily replay years later triggered by scenes such as oj maintaining he did not slice nicole’s throat or wesley snipes on the silver screen bigger than life kissing a white woman who favors irma singletary, your daughter’s friend who divorced a black man after he beat her one night and she refused to press charges against him the next morning?

in many of those garish photographs there are a lot of people standing around. i wonder how many among those audiences are alive today, driving america’s streets and buying christmas gifts?

3.

richard hammonds was a handsome man. he was moderately intelligent. could work hard but really didn’t like to exert his body to the point of sweating. believe it or not what he was really good at was leather work. give him a piece of leather and his tools and he could make anything from shoes to hats and everything in between. and he would do it well, so well that a number of people have been buried wearing shoes richard had made—their family knew how proud the deceased had been of richard’s handicraft, so that’s what the corpse wore at the funeral.

for example, brother james sweet—his name was actually james anthony johnson but, with a twinkle in his eye, he would raise his left hand, flashing his ruby and diamond pinkie ring, graciously tip his every present gray stetson, and, in his trademark rumbling baritone, request that you call him “james sweet, bra-thaaa jaaaames sweee-eat, cause i’m always good to womens, treats children with kindness and is a friend to the end with all my brothers”—well, brother sweet had instructed everyone of concern in his immediate family to bury him in his favorite, oxblood loafers that richard had hooked up especially for sweet. there were no shoes more comfortable anywhere in the world and he, sweets, which was the acceptable short form of brother sweet, certainly didn’t want to be stepping around heaven with anything uncomfortable on his bunioned feet (nor, likewise, running through hell, if it came to that—and he would wink to let you know that he didn’t think it would come to that). of course, at a funeral you don’t usually see the feet of the recently departed but that was not the point.

the point is that people were really pleased with richard hammonds’ handiwork. unfortunately, in terms of a stable income, although richard hammonds excelled at making leather goods, what he actually loved to do was watch and wager on the ponies. and since he lived in new orleans and the fair grounds racetrack was convenient, well, during racing season, which seemed to be almost year round, richard spent many an afternoon cheering on a two year-old filly while his workbench went unused.

fortunately, richard hammonds seldom wagered more than he could afford to lose and on occasion won much more than he had gambled for the month. however, winning at the racetrack was uncertain. no matter what betting system he used, richard could never accurately predict when he would win big or how long a loosing streak would maintain its grip on his wallet.

routinely, richard would do enough leather work to pay the house note and give eileen an allotment to buy food and then it was off to the races. needless to say, had eileen not worked as a seamstress at haspel’s factory in the seventh ward, this would have been an unworkable arrangement.

but richard hammonds didn’t drink more than a beer now and then, went to mass every sunday morning, and was moderately faithful, so what could have been a precarious and intemperate social situation settled into a predictable and manageable state of affairs until richard was wobbling home one october evening—he had had a very good day and had indulged in a few drinks at mule’s, in fact, he had even bought a round for the guys and stashed a small bundle in his hip pocket for eileen and still had in his inside jacket pocket enough money to pay for every bill he could think of.

when the police stopped richard his explanations of who he was, where he had come from, where he was going and how he came to have so much cash weren’t sufficient to please the two officers who were looking for a middle-aged colored man who had robbed and raped a woman over in mid-city.

we do not have to go into any details. the focus of this story is not on the beating, the injustice of his subsequent death, or even the condemning of the two police officers. remember we are concerned with death, and the question is: when, if ever, did richard know he was going to die and what was his reaction, or more precisely, what were his thoughts about that awful fact, if indeed he ever realized the imminence of his demise?

4.

everybody, sooner or later, thinks about dying. for many african americans there is even a morbid twist on this universal reflection on the inevitability of mortality. for us, it is not just a question of when we will die but also a more thorny question, a question we seldom would admit publicly but one that at some occasion or another consumes us in private: would i be better off dead? if you had been reared black in pre-sixties white america, sooner or later, you probably looked that thought in the eye?

however, the universality of death thoughts notwithstanding, there is a big difference between abstract speculation about the eventuality of death and the far more difficult task of confronting the stale breath of death as it fouls the air in front your nose. death is nothing to fuck with. indeed, actually facing certain death can make you shit on yourself, particularly if death not only surprises you but also perversely gives you a moment to think about crossing the great divide. like when a lover in the throes of getting it on, sincerity announces through clenched teeth that they are about to come, you respond as any sensible person would by doing harder, or faster, or stronger, or more tenderly, more intensely, more whatever, you increase the pressure and help usher that moment, well, when it’s death coming what do we do, do we rush to it, or do we withdraw from it? don’t answer too soon. think of all the people you have heard of who died as a result of being some place they really shouldn’t have been, being involved in some situation they should never have encountered, at the hands of someone whom they should never have been near. think about how often we die other than a natural death—and then again, what death is not natural, because isn’t it part of human nature to die, and to kill?

richard never expected to die on that day, especially since he had just experienced the good fortune of a twenty-to-one long shot paying up on a fifty dollar bet. even when the tandem took turns trying to beat a confession out of him, even after his jaw was broken and he could only moan and shake his head, even then richard still didn’t think of death. he was too busy dealing with pain. when they put the gun in his mouth, he perversely thought, “go head, pull the trigger, that would be better than getting beat like this,” but even then, richard didn’t really expect to die. he just wanted the beating to be over and if it took death to end it, well, he was feeling so bad he thought that death might be preferable. yet, richard didn’t really think he was going to die. in fact, as is the case with so many of us, richard died before he realized they were going to kill him.

we blacks wonder about fate and destiny, justice and karma. sometimes there seems that there is no god, or rather if there is a god then he is capricious with a macabre sense of humor—we grant him humor because to think of god without humor would be to concede that we are at the mercy of a monster who enjoys literally tormenting us to death.

which brings up another question, would we procreate if it were not so pleasurable? if sex didn’t feel good, would we bother with conceiving children? for many of us the answer is obvious; of course, we wouldn’t. that’s why birth control was created—to protect us from disease and children, to make it possible for us to enjoy the pleasure of sexual procreation with none of the responsibilities of child rearing. which means that the drive to have children may in fact not be as strong as we have been led to believe, or maybe, it’s simply that in modern times we have been conditioned to think only of ourselves—the personal pleasures. but the question i really want to raise is this: what if death were pleasurable would we end ourselves? what if it felt really good to die—not just calming but totally pleasurable?

of course, richard was not thinking any of these sorts of questions as the two officers smashed in richard’s face. formal philosophy is a task engaged in by those for whom survival is not a pressing issue.

5.

every age, every people, every society has an ethos—a defining spirit. and this spirit expresses itself in sometimes odd and fascinating ways. for much of the 20th century the ethos of african americans was one of contemplating the future with a certain optimism. why else march through the streets of birmingham, alabama and sing “we shall overcome” to bull connor, a man who was not known for any appreciation of music?

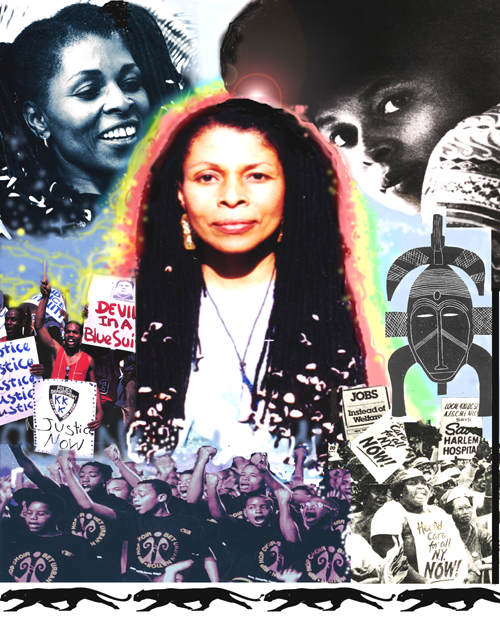

the birmingham of bull connor was just about half a century ago. during that period when bombs regularly sounded throughout birmingham and the deep south, if you go back and look at the pictures of black people of that era when they posed for a portrait, especially if they were college educated, you will invariable spy among the men what i call the classic negro pose of hand to chin in contemplation. a variation is one temple of a pair of glasses held close to or between the lips; then there is the pipe firmly grasped, not to mention the college diploma held to the side of the head like a sweetheart—these are iconic images of optimistic negroes, images that capture the ethos of their era.

today, the hand has moved from the chin. we no longer pose in contemplative ways, what is cropping up more and more is the hand to the crown of the head, not in a woe is me posture, but more like: damn, this is some deep shit we’re in.

unconsciously, during a recent photo shoot, i ended up in that pose. when the picture was published i was mildly surprised, i did not remember adopting that look of serious concern. but just because i don’t remember it does not mean that it didn’t happen. clearly it happened. there is my unsmiling portrait. and i see that pose more and more, particularly when i look at the publicity shots of writers. we are children of production—we are shaped and influenced, even when unconscious of it, by the prevailing ethos. a lot of us look like we are gravely weighing the upsides and downsides of both life and death.

and when people tell you how much they like that photo, then that tells you just how much the photo reflects our current contemplation of death. in those photographs rarely are we smiling. our eyes are wide open. we are not dreamy eyed romantics. we are not lost in meditation. we are looking at death. the disintegration of our communities, the fissure of our social structures, the absence of lasting interpersonal relationships, the proliferation of age and gender alienation. the death of a people.

and when i took my photo it was supposed to be a happy occasion. but obviously the myth of the happy negro is long gone.

6.

i wonder when the old man put the gun to his head did he hold his head with his free hand?

7.

richard couldn’t put his hands to his head because his hands were handcuffed behind him.

8.

which story seems more plausible: the old man or richard? is it not odd that by piling up details and framing the story in a believable context it is relatively easy to believe that richard hammonds actually died as a result of a police beating and shooting in the late fifties in new orleans? and that the old man seems to be a metaphor. but an old man (whose name i don’t want to reveal because it would add nothing to our story) actually killed himself during the christmas holidays (of course i speculate and fictionalize a lot of the old man’s story, but the suicide actually happened) and the story of richard hammonds is totally fictitious except for the cops who killed him—cops did kill negroes in new orleans.

9.

the old man and richard hammonds had gone to high school together, and gone to bars together, making merry, drinking and acting mindlessly stupid on a couple of occasions. they had double dated a couple of times, and had once even engaged in sex with the same woman (at different times, months apart, but the same woman nonetheless—she remembers the old man as the better lover because he was more tender, seemed more sincere.

(there had been this untalked about but often expressed rivalry between richard and the old man. close friends are often bound by both love and jealousy, so there was nothing unusual about them being attracted to the same woman. but remember richard was the handsome one. he was also glib, perhaps because he learned how to hold back his feelings. he could talk a woman into bed, or more likely the back of a studebaker—richard’s father worked as a pullman porter and made nice money for a colored man and had bought a car but was often not in town to enjoy the car and richard, though he didn’t personally have much money, did have access to the car. anyway, richard never thought about what the women he bedded in the back seat thought about before, during or after he bedded them. after all it was just a moment’s pleasure.

(but the old man, well, he was a young man then, he thought about how other’s felt about him a lot, and though he fucked mildred, it was not because she was available but because he was really, really moved by mildred and told her so. told her, “girl you moves me.”

(“i do?” she was used to men wanting to sex her, but not to men admitting that they were deeply affected by her.

(“yes, you does,” and he twirled her at that moment—they were dancing and he was whispering in her ear, dancing in a little new orleans nite club, to a song on the juke box—he twirled her. and smiled. and she had never been twirled quite like this gracefully dancing young man twirled her. and when she reversed the twirl and spun back into his arms, he momentarily paused and said, “i wish i could dance with you all night.”)

the old man had not been angling to get her in bed, he was just genuinely enjoying her company. he liked to dance. she liked to dance. they were having a good time. and when somehow they ended up making love on the sofa in her front room that night while her sister and her sister’s children soundly (he hoped) slept two rooms away, he had been a little nervous at first.

her softness felt so good, before he knew it, a little cry caught in his throat. he was trying to be quiet, but goodness and quiet sometimes do not go together. i mean, you know how good it hurts to hold it in? well the possibility that the sound of your love making will disturb and awaken others nearby, that anxiety about discovery adds to the covert enjoyment. so, instead of surfacing upward through his throat, the cry was redirected down into his chest, but it bounced back and was about to pop audibly out of his mouth. mildred felt that sound about to pour forth like a coo-coo clock gone haywire, and with the mischief that only a woman can summon she cupped one hand tightly over his mouth and with her other hand reached down and gently squeezed his testicles.

ya boy liked to died. he shuddered. he couldn’t breath. her hand tightly covered his mouth and partially blocked his nose. and he was coming like mad. and he moaned a stifled moan, air yo-yoing back in forth between the back of his mouth atop his throat and the near bursting constriction of his chest. finally, he wheezed gusts of exhales out of his distended nostrils, which flared like those of a race horse heaving after a superfast lap. and then he cried out and tried to call back the sound all at the same time. and that was followed with another terrible quake. in a semi-conscious state, he lay helpless, wrapped up in the murmured laughter of mildred’s playful passion.

but he didn’t hear her soft, soft laughter. he didn’t hear anything. he was totally out of it. he was struggling to catch his breath, in fact had almost slipped off the large couch—if her legs had not clamped around him so firmly, he would have tumbled to the floor. after that he didn’t distinctly remember anything until he woke up the next morning, at home, in his own bed and didn’t know how he got there. he must have walked home or something, but all he could remember was her softness, her touch, his lengthy orgasm (he had never come that long before), and the way her legs held him when he almost fell over. you can easily forget a short walk home, but there are some experiences that are so sharply etched in the memory of your flesh, those encounters you never forget.

a couple of days later when richard asked the old man about mildred, whether they had done it, the old man had said, “no, we just had a good time dancing and i took her home. then i went home.” richard had replied, “you should have got it, she likes you. i got her drunk and got it once but she never would let me get no mo. but she likes you. you should get it.” the old man had said nothing further, merely looked away, certain that richard would not understand that what the old man felt for mildred, although initiated by the sharpness of their sexual encounter, was, nonetheless, a feeling deeper than a good fuck.

many years later, when the old man was watching the house of representatives vote to impeach bill clinton for lying to the american people about the monica lewinsky affair, something terrible took hold of him. although he continued to see mildred for over twenty years and even had a kid with her, the old man had never told his wife. and he felt intensely guilty. intensely.

he felt horrible. felt like he had felt at richard’s funeral. sitting in the catholic church before a closed casket. the body had been too brutalized to have a public viewing. the police had shot his good friend richard, shot him in the head.

while he sat between his wife and two daughters on one side and his young son on the other side, the old man was thinking about his dead friend when he looked up and saw mildred looking over at him with those large, limpid, brown eyes. nearly every time he stole a glance her way, she seemed to be looking directly at him. he could not read her eyes.

but his friend richard was dead. and his wife and legitimate children were at his side and his woman was across the isle staring at him, and the old man felt really guilty about how he was living his life, and he put his head in his hands and just wanted to ball up and die. and he didn’t realize he was crying until his wife daubed his face with her handkerchief.

10.

a murder is a crime against society. we look at pictures of murderers and wonder about them. wonder what led them to do it. wonder do they have feelings like the rest of us.

what motivates one human to lynch another?

in the case of a suicide, everyone who survives wonders not only what led to the murder but also, particularly for those who were close to the victim, we wonder what could we have done, what “should” we have done to prevent the murder.

murder is a crime condemning society and suicide is particularly damning of those who were close to the murderer (who is also the murderee). if you think about someone close to you committing suicide, you have to ask yourself, what did i fail to do that would have prevented that person from committing self-murder? while sometimes we ask that question of a mass murderer—what could have been done to prevent them from acting the way they did—we always ask that question of a suicide. and why? if we can not stop people from committing large and impersonal murders, how can we hope to stop small murders, the most personal of murders: the suicide? the question is perplexing.

after awhile though, you come to an awful realization: maybe it is impossible to stop people from killing each other and themselves. indeed, is it not a certainty that it is impossible to stop suicide?

11.

if you are shot in the head with a large handgun it can be messy.

12.

if you shoot yourself in the head with a large handgun it can be messy.

13.

the old man’s casket was sealed before the funeral mass just like richard’s had been. a closed casket is a terrible death for it is a death which suggests that this death is much more worse than ordinary death. this is a death you can not look in the face. and what can be more horrible than imagining how horrible death looks when the corpse is too horrible to look at?

14.

mildred was at the old man’s funeral. so was their son who favored his mother but had his father’s skin color. mildred had not talked with the old man in over two months, and then it was only briefly over the phone. he had said something about being sorry he had never been brave enough to marry her. and hung up. mildred had waited in vain for him to call back. as anxious as she had been, she had never once broken their agreement. she knew where he lived, knew his phone number, but she never called. never. and now he was dead, gone. life is so cruel, especially when much of your life is lived cloistered in a box of arrangements shut off from what passes for normal life. to everyone mildred looked like the statistic of single mother with one child: a son, father unknown. but what she felt like was a widow, a widow whom had never been married but a true widow nevertheless, her de facto husband’s corpse sequestered in a closed box, not unlike her whole life, lived unrecognized outside of sight. issac (mildred and the old man’s son) used to ask who his father was, but he stopped asking after weathering junior high school taunts. and once he was married and had children of his own, he understood that what was important was not who his father had been but what kind of father he would be for his children. when his mother called and asked him to accompany her to the old man’s funeral, issac at last knew the answer without ever having to rephrase the question. mildred and issace both remained dry-eyed throughout the service even though inside both of them were crying like crazy.

you can not gauge the depths simply by looking at the surface. printed on the program was a smiling snapshot of the old man. next to the closed casket there was an enlargement of this same posed photograph. but what picture of the old man was in various people’s mind?

moreover, what does a self murderer look like whose death has left the corpse too gruesome to witness? certainly not like the smiling headshot on the easel surrounded by flowers.

was the look in the old man’s eye as he pulled the trigger anything like that wild look in the eyes of white people staring at a lynched negro—of course not? but what did he look like looking at his own death?

15.

have you ever seen a picture of the man who was convicted of bombing the baptist church in birmingham, alabama and killing those four little girls? he looks like a white man. and once you get beyond the racial aspect of the murderer, he looks like a man. and once you get beyond the gender aspect of the murderer—a grown man killing four little girls—well, then, he looks like a human being. murderers are human beings. they look like what they are. it is a conceit to think that murderers look different from “ordinary” human beings. what does a killer look like? look at the nearest human being.

16.

while i admit i have not seen a lot of pictures of white people—and then again i have undoubtedly seen more pictures of white people than of black people when you consider how the image of whiteness surrounds us and bombards us in school, in commerce, in television, in entertainment, in advertisements, everywhere—but anyway, i don’t remember seeing many white persons in the classic negro pose of yore nor in the contemporary iconic hand to the crown of the head pose.

in examining the photos of lynchings i see none of the concern for the future that the hand to the head would indicate. that hand to the head indicates that a person has a heart. that a person is feeling life, and though the life that is felt may not be pleasant, at least we are still feeling.

but when you watch and listen to and smell a person dying, and when you cut off your feelings for the fate of another human being, well...—and you know it is not biological. have you read about the civil wars in africa typified by the hutu vs. tutsi conflict? how literally thousands of people are hacked to death. it is one thing to fire a gun or drop a bomb, it is another thing to whack, whack, whack with a machete slaughtering a human being as though assailing a dangerous beast or a tree that was in the way of progress. when any of us, be we white, black, or whatever, when we severe our feelings to the point that not only do we methodically and unfeelingly commit acts of mass murder or acts of ritual murder, when we can watch murder and not feel revulsion then obviously we have moved to the point that death gives us pleasure.

when i first raised the issue about death and pleasure you may have thought, “oh, how absurd.” but the next time you are chomping your popcorn and sipping your artificially flavored sugar water while watching thrilling scenes of mayhem, murder and mass destruction on the silver screen (perhaps i should add that you have paid for the privilege of this pleasure), but the next time the bodies fly through the air, the bullets rip apart a young man in slow mo, the very next time you watch an image of death and get pleasure from it, see if you can remember to say “oh, how absurd.”

i think you won’t be able to, any more than at the moment of orgasm you would holler “oh, how absurd.” for you see pleasure in and of itself is never absurd, perverse perhaps, but never absurd. and taking pleasure in someone else’s death: oh, how... what? how do we describe that pleasure? what is human about enjoying death? or perhaps, since deriving pleasure from someone else’s demise seems to be a norm today, maybe i should ask, what is inhuman about enjoying death?

there is much that is wrong.

—kalamu ya salaam