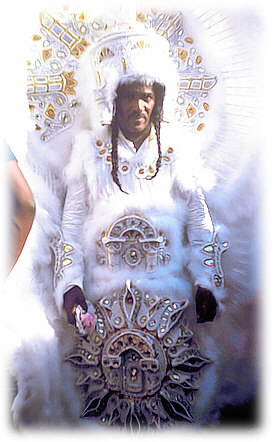

photo by Alex Lear

It didn't jes grew:

the social and aesthetic significance

of African American music.

Our music is our Mother Tongue, our meta-language that we use for the fullest expression of self. In the preface to Paul Garon's seminal text on surrealism and Black music, Blues & the Poetic Spirit, Franklin Rosemont notes that

. . . American black music originated in the culture of the slaves who were systematically deprived of the more "refined" instruments of human expression. Slaves were forbidden to learn to read or write, and they had no opportunity for plastic expression. Even their musical efforts were severely circumscribed; slaveholders who feared the use of drums and other instruments as means of communication between slave assemblies, and hence as tools of insurrection, banned such instruments from the plantations. Thus the spoken word, the chant, and dancing were the only vehicles of creative expression left to the slaves. The sublimative energies that in different conditions would doubtless have gone into writing, painting, sculpture, etc. were necessarily concentrated in the naked word and the naked gesture - in the field hollers, work-songs, and their accompanying rhythmic movements - in which gestated the embryo that would eventually emerge as the blues. Black music developed out of, and later side by side with, this vigorous oral poetry combined with dancing, both nourished in the tropical tempest of black magic and the overwhelming desire for freedom. The extreme repressive context of its origins, and its consequent subsumption into itself of the whole gamut of creative impulses, together give the blues its unique intensity and distinctive poetic resonance

As a living and fertile body of creative expression blues and jazz retain today their boundless integrity and provocative flare. Their role in shaping the modern sensibility is already large and shows every sign of expanding. It should be emphasized, since so many critics pretend not to notice it, that all authentic blues and jazz share a poetically subversive core, an explosive essence of irreconcilable revolt against the shameful limits of an unlivable destiny. Notwithstanding the whimpering objections of a few timid skeptics, this revolt cannot be "assimilated" into the abject mainstream of American bourgeois/Christian culture except by way of dilution and/or outright falsification. The dark truth of Afro-American music remains unquestionably oppositional. Its implacable Luciferian pride - that is, its aggressive and uncompromising assertion of the omnipotence of desire and the imagination in the face of all resistances - forever provides a stumbling-block for those who would like to exploit it as a mere commercial diversion, a mere form of "entertainment," a mere ruse to keep the cash register ringing. Born in passionate revolt against the unlivable, blues and jazz demand nothing less than a new life. (7-8)

Within the above stated context, this paper will address language as both a basic means of communication and as a tool for artistic expression; the foundational aesthetics of African American music, which I refer to as GBM (Great Black Music); and the state and significance of the four major genres of GBM in the contemporary setting - Gospel, or religious music; Blues; Jazz; and Black Pop or R&B, which includes everything from Jump Blues, Doo-Wop, Soul, and Funk to New Jack Swing and, arguably, Rap (as an extension of R&B).

This essay is an attempt not simply to explain what GBM is and how it functions within the Black community, but to contextualize both the total significance of and worldview implicit in GBM.

The term Great Black Music is not a racial term, even though it contains a racial element. When African Americans refer to someone as Black, we generally mean a lot more than race; after all, we are a mixture of races. So the biological is the least important of the three elements of Blackness. Culture and consciousness are the critical elements. Culture roots the individual in a group, a community of people who share behavior, attitudes, ethos, and ideals. Consciousness is critical because an individual can be biologically Black and Black-acculturated by rearing, but still serve as a representative of some other culture. Just because a Black person does something does not make that act or creation representative of Black culture.

I Heard That

Let us start with who African Americans are, how we as a people became ourselves. And let us recognize an obvious but often overlooked reality: Standard American English (SAE) is not the native language of African Americans, even though a kreolization of SAE is the language we grow up with and use on a day-to-day basis. We use English because it was forced on us by a dominant culture. Unlike other immigrants who came to the United States, African Americans (and, in a similar way, but not to so great an extent, Native Americans) were denied the opportunity to use on a day-to-day basis, and thus retain, their native languages.

Some would argue that, while the above may be historically true, in contemporary settings SAE is our native language. I argue that a "native tongue" is not imposed, but rather developed. Moreover, those of us who are not formally educated in SAE beyond the rudiments of grammar tend to speak an Africanized form of SAE.

Formally speaking, SAE is literally a foreign language, inexact and inadequate to express fully the human-rainbow totality of our essence as a people. The lexicon and grammar of SAE can not communicate the essentials of our experiences precisely - in part because SAE was the language devised by those who actively conspired to forcibly deny our humanity and ensure our continued subjugation.

Our national identity as a people was forged in the kiln and on the anvil of the greatest holocaust in human history: the colonization of the Western hemisphere (especially the genocide of Native Americans and the chattel enslavement of Africans). The English language specifically ignores, obfuscates, misrepresents, or negates this reality. There are literally no SAE words to describe adequately the social and psychological history of our people. Indeed, SAE is overwhelmingly anti-"Black." Just as all languages propose a worldview and value system, SAE (like all other colonial languages) presupposes the domination of people of color by Europeans and the hierarchical subservience of all things African to anything European.

But although we were denied expression of our native languages, being the creative people we are, we not only developed our own approach to the master's tongue, but we went one better: We created a nonverbal language which expressed our worldly concerns, as well as our spiritual aspirations. This language we created is "the music."

More than any other form of communication, "the music" expresses, at the deepest levels, the realities of our existence. The most profound and serious moral lessons are generally articulated by the speaker shifting into the "talk-singing" style of orature that is an extension of GBM. All of our ways of expressing our concerns, what is on our minds and what is happening, appear in the music long before they are codified in literature, dance, film, or the visual/plastic arts. On a personal level, we find ourselves using song lyrics as encoded metaphors to express the epiphanous moments of our lives, especially as the moments concern our interpersonal relationships. We will literally break out in song and nobody - not even that person walking past you on the street as you moan, "First you love me / then you snub me" - finds this unusual. We understand because the music is our mother tongue, even those of us who otherwise eschew any use of the vernacular.

At the same time that I celebrate "the music" as our "mother tongue," like most people of color, I recognize that African Americans from birth grow up speaking a second language, a variation of SAE, the trade language of our times. Those who argue that we are now simply American citizens and not colonial subjects transformed by nearly a half-millennium of colonization are very precisely and ahistorically attempting to redefine our reality and deny the circumstances and legacies of chattel slavery.

The Mother Tongue and the Other Tongue

I start with the language issue because I believe that a full appreciation of our music is incomplete if the appreciation does not identify GBM as our "mother tongue," the language we use for the fullest expression of ourselves. Put simply, "the music" is where our soul is. With other people you might have to view paintings and architecture, or learn to "read" their literature. With our people, in order to fully appreciate us, one must immerse oneself in our music.

Africans in the diaspora are probably the only modern people whose soul is expressed almost solely through our music. On the African continent, sculpture (and specific crafts ranging from textiles to ceramics), dance, and sociological ritual systems represent defining expressions in addition to music. But in the diaspora, where our people were uniformly denied the opportunities of concrete expression and mass assembly, all our soul was poured into the ephemerality of music.

Indeed, it is possible to know and understand African Americans by studying our music and its history without ever reading a novel or viewing a piece of art - especially since the most successful of all our other art forms owe some measure of their inspiration, if not their articulation, to the influence of GBM on the artist.

Not only is GBM our most identifiable and most developed cultural expression, but, within the context of world achievements, GBM is far in advance of the other art forms. In fact, while we have barely penetrated world consciousness in terms of other forms, we dominate world consciousness in terms of music. Not even in the area of dance (which is so closely aligned to music) have we made a comparable world impression. This is no accident, but a specific reflection of the high development of music within African American culture and the dwarfing of all other forms of artistic expression.(1)

This reality is partly due to the constrictions of enslavement and colonialism. Music, sound could be created at anytime, under any conditions with only the most primary of instruments - i.e., the voice (lyrics/melody) and the body (beats/rhythm). Chained naked to a tree or a rock, our ancestors could still make music. Plus, because of their own opinions about music, our captors had little idea that music could be expressive language and hence a tool of resistance, and even rebellion. (The colonialists of America did understand enough of the power of our music that in the ante-bellum era they universally feared and legally prohibited our use of the drum outside of well-monitored special occasions. Thus, within GBM, rhythm, although sometimes sublimated, becomes one of the major cultural battlegrounds.)

Every era of our music has an identifiable rhythm. This is even the case with the religious music. So on the one hand the drum is repressed by the dominant society, and on the other hand the drum is recreated by proponents of GBM who understand (sometimes intuitively, sometimes consciously) that rhythm is the battleground.

Heads up: Why do I claim GBM as the "mother tongue" and "SAE" as a second language, with what was once called "Black English" as a third category somewhere between the two? GBM was developed as a language of communication and cultural affirmation among ourselves and specifically for ourselves. "Black English" was our means of day-to-day communication among ourselves about mundane and ordinary matters. Our use of SAE existed strictly for the purpose of communicating with our captors or as an indication that we had successfully adopted the ways of our captors and hence were not like "most Blacks" - indeed, were almost "White."

From a linguistic standpoint, to become "White" is to strip oneself of any "foreign" languages that might be one's birthright and also to strip oneself of foreign accents. Linguistically, to be White means to speak SAE flawlessly. Even when it appropriates Eurocentric musical instruments or modes of music making, GBM never aspires to be White. Listen to the music, especially unmediated by dominant-society audiences, recording companies, or aspirations, and you'll hear what I'm saying.

As Geneva Smitherman perceptively notes,

African slaves in America initially developed a pidgin, a language of transaction, that was used in communication between themselves and whites. Over the years, the pidgin gradually became widespread among slaves and evolved into a creole. Developed without benefit of any formal instruction (not even a language lab!), this lingo involved the substitution of English for West African words, but within the same basic structure and idiom that characterized West African language patterns. . . . The formation of this Black American English Pidgin demonstrates, then, simply what any learner of a new language does. They attempt to fit the words and sounds of the new language into the basic idiomatic mold and structure of their native tongue. . . .

The slave's application of his or her intuitive knowledge of West African rules to English helped bridge the communications gap between slave and master. However, the slaves also had the problem of communicating with each other. It was the practice of slavers to mix up Africans from different tribes, so in any slave community there would be various tribal languages such as Ibo, Yoruba, Hausa. Even though these African language systems shared general structural commonalties, still they differed in vocabulary. Thus the same English-African language mixture that was used between slave and master had also to be used between slave and slave. All this notwithstanding, it is only logical to assume that the newly arrived Africans were, for a time at least, bilingual, having command of both their native African tongue and the English pidgin as well. However, there was no opportunity to speak and thus reinforce their native language, and as new generation of slaves were born in the New World, the native African speech was heard and used less and less, and the English pidgin and creole varieties more and more. (5-8)

Understand that we are talking about a process of generations, of centuries, not simply a decade or two. Also understand that many African languages were tonal - when West Africans talk, it's almost like singing. Finally, understand that music was integral to most social activities in West Africa. These things allow one to appreciate that the dynamics of the development of language apply very specifically to the development of GBM, especially after the Civil War when African Americans had some measure of freedom to engage in self-defined cultural expression. It is only common sense that the musical cultural expression of newly emancipated African Americans would be very different from, if not outright at odds with, the music of our historic captors, even though the music would also be adaptive of instruments and modalities of musical articulation (especially "melodies") of the dominant society. Additionally, we should keep in mind that a significant number of the newly emancipated creators of GBM were either first- or second-generation American-born and thus would have had a high degree of African cultural retention, especially in terms of music.

In this context, it is apparent that there was no pressure or inclination for early Gospel, Blues, Jazz, or R&B to uphold standard English vocabularies or musical modalities. Indeed, Jazz in particular and the other three genres in general self-consciously differentiate themselves from SAE, and from the dominant modes of American and European music-making, through the use of an indigenous vocabulary, a culturally specific syntax, and a desire to break past the formal structures of the existing language.

This is not just a case of being "ignorant" or "emotional." It is a conscious choice to create an alternative language of communication, a language which is expressive and affirming of the colonized rather than expressive and affirming of the colonizer.

It may seem a bit "inaccurate" and "off-putting" that I keep using terms colonized and colonizer, especially since, after 1865, African Americans have legally and culturally been citizens of the United States. But there are many of us who want to retain our culture of resistance and alternative rather than be about submission and assimilation. For us, the re remains a raw element in our cultural expression precisely to remind us who we are, and to affirm that we do not ever want to forget or give up the fight against our condition of forced submission to alien conquerors.

This is why in many of our native vocabularies, when speaking of Whites in general, the vocabulary is one of opposition - e.g., the "ofay" (pig Latin for 'foe') of bebop and the "honky" of the Black Power Movement. This historic oppositional stance often seems to be in direct contrast to the higher morality of calls for mutual respect and racial harmony. But calls for harmony which do not address reparations and rectification of massive historical inequities are, at best, "idealistic" and more often than not downright "duplicitous," because such calls refuse to take into full consideration African American historical and contemporary political and economic realities.

This attitude of cultural warfare is indelibly encoded in the mother tongue of GBM and in "Black English." Conversely, opposition to this philosophical position is encoded in SAE. This is the fundamental cultural dichotomy: GBM, the mother tongue, through its intrinsic oppositional stance, is first and foremost a culturally specific affirmation of the humanity of African Americans, the same people whose humanity SAE attempts to negate.

The Philosophical Attributes of GBM

In this affirmation/negation dichotomy is precisely where the philosophical attributes of GBM are located. At root GBM is always loud, raw, bluesy, and iconoclastic; it is a break with the status quo yet an extension of tradition; it is democratic in execution yet solicitous of the unique contribution of the individual; and it is celebratory of the present and adaptive to current conditions hence the emphasis on compositional and articulational improvisation (i.e., the music is composed as it is created, and articulated as improvisation based on the realities of the moment rather than as a written score). At root GBM is a music which is both naive in its emphasis on emotive prowess and modern in its advocacy of participants' equality.

Loud. Dynamic is not inexact, but loud carries a connotation of disruptive of the status quo. If we thus read loud to mean 'disruptive,' then clearly in musical terms rootsy GBM is quite loud. Part of it springs from the desire to create overtones and feedback, and a desire to actually "feel" the vibrations of the music: low-frequency drums and bass instruments, falsetto horns and voice - all setting in motion vibrations which literally "rock the house" and encourage shouted response. This extremely dynamic element of feedback (as in call-and-response both from the audience and from the instruments themselves) and of physical movement is manifest whenever "the music gets good."

Unlike classical European music which one contemplates in silence and stillness or in highly structured dance movements, GBM demands response and movement. While silence can be part of loudness, most of the techniques associated with GBM, particularly at the roots level, emphasize an articulation that is physical and rhythmic, regardless of the instrument used.

Moreover, this "loudness" tends to disrupt calm expression and require accommodation of accidents of the moment. In fact, by being loud, the music actually (and consciously) causes unplanned responses so that those responses can be subsumed into the resultantly transformed totality. In a sense, the music does not fully become itself until it literally vibrates its environment and its audience causing both to participate in the music making.

Everything from "tearing the roof off the sucker" to "burning down the house," "smoking" and "cooking" or "wreaking maximum effect" - all connote physical transformation of the structure or environment where the music is made and not just the emotional transformation of the audience that is present when the music is being made. While it is possible to effect this desired transformation while playing softly, in general there will even be a loudness to the silence that is played the silence becomes not an absence of sound, but rather a powerful damming of sound that physically and momentarily hold s the noise at bay.

Raw. As in the case of soft and loud, raw as a quality operates with refined in a both/and dialectic rather than an either/or duality. Rawness is achieved at the moment of creation, not after a period of reflection. Even music that starts off refined will strive to achieve a point where the response is spontaneous and unpremeditated. Philosophically, this is a "come as you are" approach that emphasizes honest involvement with the music making. The acceptance of rawness also means that no one is excluded because of social considerations. Raw accepts one at whatever level one exists. Raw also emphasizes "honesty" over "correctness," sincere response rather than intellectualized observation.

Raw is always uncivilized, unmediated by social convention. Again, listen to the music at the root level and you will immediately hear what I am talking about. There is almost an urgency of the now time, which reflects when we want to be free: now, not later. Rawness openly reveals what has been socially repressed/oppressed/exploited - at least with urgency, and often seemingly with fury or anger.

Bluesy. The Blues is an attitude of transcendence through acceptance, but not submission. We can accept reality without submitting to it: In fact, we sing Blues songs to transform that which we accept - namely our reality. Conversely we can submit to a reality and not transform it, which is what I call singing "straight" and "proper" with nary a bluesy inflection. In the lyrics of traditional Blues songs, there is generally a stated desire to rise above the situation at hand, to transform the situation (with violence if necessary), or at the very least a looking forward to better times.

In traditional Gospel, the bluesy sound focuses on deliverance and transformation in the other world. In traditional Blues, the focus is deliverance and transformation in this world. Both offer a spiritual response to a negative social situation, supposing that if one can not overcome physically, then psychologically (or "spiritually") one can transcend the limitations of reality.

From a musicological standpoint, a bluesy sound exists outside of the specific tones associated with Western musical scales. There is an inexactness to the bluesy sound: a quavering between set nodes; a sliding toward or away from the desired note; a use of noise elements and objects to alter the sound (e.g., rubber, metal, and glass mutes; bottlenecks, knives, the hand or other body parts covering the bell or sounding boards of the instruments, etc.); unorthodox playing techniques; exaggerated vibrato and various other devices that produce a "dirty" tone.

This "dirty" or bluesy tone approximates the social reality, which is one of chaos and struggle rather than order and stability. The articulation and attempted resolution of the chaos, of course, involves a transitory, give-and-take process, because in reality we are still dominated and thus, regardless of successes and victories, on a social, political, and economic level we are still very much in a period of chaos.

Even those of us who are consciously attempting to assimilate are in a state of chaos, because integration is won at the expense of repressing our "native" identity and is also always threatened by the inability (and/or unwillingness) of the majority of our people to assimilate fully. We are faced with the chaos of the self as a collective identity which revels in resistance and sometimes wallows in submission, or the chaos of the self as an individual identity, an "emancipated" but not "liberated" individual self which achieves a measure of freedom by literally severing its identity from the group which gave that self life. This is the chaos which is articulated in GBM as a loud, raw, and bluesy sound.

In "the blues aesthetic," the opening essay in my book What Is Life?: Reclaiming the Black Blues Self, I offer a "condensed and simplified codification of the blues aesthetic" which further explains the philosophical ingredients of the bluesy sound:

1. stylization of process - i.e., whatever blues people did, it was done with a style and emphasized the collective tastes and simultaneously demonstrated the individual variation on the collective statement. this practice, of course, is based on call/response motifs but might more accurately be identified as theme/variation. if you know the history of the music, the use of theme/variation marked the movement from agrarian (communal) forms to urban (collective) forms. the communal form required the audience. in the collective form, the artists became their own audience, and the audience moved from communal participant to observer of the collective, from proactive participant to quasi-passive observer, from ritual to entertainment. . . .

2. the deliberate use of exaggeration to call attention to key qualities, with wit being one of the most salient projections of exaggeration. . . . (ever wonder why some people miss a joke that is really obvious? if you don't know the reality, you can't appreciate the joke, precisely because the joke is a comment on the reality.)

3. brutal honesty clothed in metaphorical grace, which includes at its core a profound recognition of the economic inequality and political racism of america. at the same time, this honesty is clothed in a profound appreciation of the fact that every strength got a weakness and that it is better to recognize (and sometimes even ridicule) rather than cover up weaknesses.

4. acceptance of the contradictory nature of life - life is both sweet and sour. while generally you got a pot of the latter, almost everybody is guaranteed at least a spoonful of the former. here one must be careful not to confuse dualism with dialectics. life is not about good vs. evil, but about good and evil eaten off the same plate.

5. an optimistic faith in the ultimate triumph of justice in the form of karma. what is wrong will be righted. what is last will be first. balance will be brought back into the world. this faith was often co-opted by christianity, but is essential even in the most downtrodden of the blues songs.

6. celebration of the sensual and erotic elements of life, as in "shake it but don't break it!" (12-14)

Iconoclastic. GBM naturally must destroy the tyranny of dominant cultural forms in order to express its true self, because the African is not European, and the African American is not White. Every social construct and/or mythological icon of the dominant culture is based on upholding the supremacy of "White" and/or Eurocentric ideals, or at least on accepting the "goodness" and "desirability" of these ideals. Thus, at every turn, in every genre, in every era, innovative GBM is seen/heard as antithetical to the musical status quo.

Iconoclasm is an organic development wherein GBM reflects the aspirations of an oppressed and exploited people. What is surprising is that the breaking of conventional structures always happens and always comes in unexpected forms. GBM iconoclasm is literally a guerrilla attack on the dominant and dominating system. Though we know the guerrillas are out there and expect that they will strike, invariably we are surprised when they do.

We should not be surprised by this inexorable law of cultural conflict. When the status quo restricts, then the articulation and affirmation of cultural expressions by those who are suppressed necessarily must take the form of demolishing the social constructs of external control.

A Rooted Departure. Here we have a contradiction which expresses itself as a dialectic, a revolutionary form of ancestor worship. GBM is always forward looking and seldom seeks to preserve or replicate the past or status quo, yet at the same time, the point of departure tends to be an extension of GBM musical traditions. From Jazz flowing out of Ragtime, to Rap sampling Funk & Rock music, a creative boldness of GBM is the way in which every new development finds some way to incorporate a previous era. Perhaps this is possible because the tradition, the previous era was, at the time of its birth, revolutionary.

Like genetic traits, the root expression can manifest itself after skipping generations. GBM stresses a connection to tradition even as it transcends tradition; it offers a musical manifestation of the African philosophical principle of accommodation and adaptation. I call it embracement because it creates something new while celebrating something old.

Embracement signifies a philosophical open-endedness which completed structure (e.g., musical compositions in which all the notes are written out, and even the inflections are directed by the composer) precludes. Embracement posits that nothing is ever finished. Each performance brings the opportunity for a fundamental development (or, conversely, a fundamental failure) to occur. This risk taking, this element of chance is intrinsic to GBM, which proposes the past as a dynamic entity: Tradition is constantly growing and being enriched.

Now Is the Time. We can't perform in the past because it's gone, and we can't perform in the future because it's not yet here, so we must perform in the present. When we perform, the question becomes whether we are trying to replicate something that existed in the past or trying to be profoundly contemporary and create a day / a music that never before existed and will never again exist in precisely the same way. In this context, principles of expression rather than specifics of expression become the measuring rod of success. Over and over, one will hear GBM musicians saying that they have no desire to play like they used to play, even though they might want to replicate a certain feeling they attained at some point in the past.

GBM, while respectful of its roots, always seeks to march forward, and in marching forward to use everything that exists as part of its arsenal of instruments and elements of music making. Literally, nothing is exempt from absorption into GBM. GBM remains identifiably itself because it adapts rather than adopts all influences. It has the capacity to deconstruct, recontextualize, and supersede the "foreign" and even "antagonistic" origins of some modes of expression which it adapts into the music.

In a profound sense, GBM does not seek to go back to Africa, but to go forward into Africa. GBM represents a transformed Africa, a sophisticated Africa, an Africa which as a result of colonialism is no longer innocent or any longer exclusively continental. In this context, there is a definite push forward to develop into something, that something being a cultural accretion, a hybrid which contains the best of everything that exists whether indigenous or foreign, originally innocuous or originally harmful.

Participatory Democracy. The emphasis on the individual differentiates GBM from traditional African musics. The phrase participatory democracy was popularized by SNCC workers in the Civil Rights Movement, and CBM's emphasis on participatory democracy (i.e., communal music making which encourages each individual to contribute creatively) is New World.

Some would say democracy in general is an American contribution. However, the fact is that America was made into a real democracy by African American struggles for civil and human rights. Left on its own, America would probably never have transformed itself into a true democracy. Thus to identify democracy in music as an American concept is misleading, unless by "American" one explicitly means a kreole society which is self-consciously accepting and respectful of its various ethnicities.

Participatory democracy encourages, even demands, open-ended contributions from all present (be they musicians or "audience members"). Participatory democracy is qualitatively different from what is generally meant by "democracy" in the American context, since each day offers a new interpretation and also new players to add to the mix. This allows for constant growth and development commensurate with the conditions of the time and the talents of the participants. These are the basic philosophical principles of GBM, which has afforded African Americans a way to elevate both the collective and the individual at the same time, in an open-ended embracement, without diminishing either.

A caveat: The above elucidated principles have been deduced from a consideration of the body of the music. I do not believe that any significant number of African American musicians create their music with these principles in the foreground of their intentions. I do not believe that any significant number of African American musicians are even conscious of these principles, or, if presented to them, that many artists would agree that these are principles governing the music they create. But the intentions and/or consciousness of the artists is not the measure of the relevance of the philosophy.

I believe that there are two ways to approach philosophy: One is to start from axioms and beliefs and try to make reality conform; the other is to create based on one's own being and social makeup and then deduce principles evidenced by what has been created. Ideologues go the axiom route, artists go the creation route. In this light, I believe a good critic should be an artist who starts by investigating what is.

If we understand nothing else, when we study Afrocentric art we must understand that everything must change. Even principles will change if the principles are drawn from the reality which we use our art to reshape. Indeed, to the degree that we are successful in changing our reality, those changes will inform and influence our philosophy. So, just as GBM has no respect for form, but loves process, our critiques are not about establishing absolute laws but about identifying a process that will guide us in interpreting and changing the world - the world that we are born into as well as the world that our art helps create.

I don't have the power to predict the future, but as a critic, I do have an obligation to understand and analyze the present and the past. Thus, this essay is meant to be open-ended and imperfect: open-ended because it is not an end in itself, and imperfect because I am ignorant of so much.

The Four Major Genres of GBM

"Why am I treated so bad?" is both a question and a statement, an existential question that has been historically phrased as "What did I do to be so Black and blue?" This questioning of causality is based on our belief in karma's truth: What goes around, comes around; what you send out is what you get back. Our belief in karma's forces causes us to wonder "What fundamental wrong did we as a people do to deserve slavery?"

"Why am I treated so bad?" is a bold statement of fact that sums up our position in this society. Except for Native Americans on reservations, we currently hold down the top spot of nearly every major negative index of social well-being by an identifiable sub-category of U.S.A. society.

The Blues aesthetic answer to our existential question is "Why not?" - life is like that, full of mysteries. We didn't earn or cause our hard luck. We didn't cause our own enslavement, even though we certainly must effect our own liberation. Christianity, however, supplies a significantly different answer: original sin - all mankind is born in sin and hence both guilty and in need of salvation.

When we were enslaved as a people, we were not yet Christians. We had our own belief systems. But in the crucible of chattel slavery, we were denied the opportunity to practice our religious rituals and retain our languages. To the degree that anything beyond subservience was taught us, we were taught Christianity, and as scholar/historian Vincent Harding accurately asserts in his important book There Is A River, although we were involuntarily conscripted into Christianity, we shaped Christianity to meet our needs and, in so doing, became the authentic U.S.A. practitioners of Christianity as a theology of liberation.

From a psychological perspective, our cleaving to Christianity is in part because it both answers the question of guilt and offers the gift of salvation, but there is also a material reason.

Except for the unique setting of Congo Square in New Orleans, Christian worship services offered the only opportunity during slavery for the expression of Afrocentric, organized, social rituals among our people. These services included the singing of hymns in a manner completely different from that in the orthodox Christian liturgy. Initially, our services were conducted under the vigilant eye of the slave master, and our hymn singing was expressly imitative of the music which we were taught, even though we always adapted and never simply adopted the teachings and modalities of worship. In Music of the Common Tongue: Survival and Celebration in Afro-American Music, musicologist Christopher Small posits that what

. . . enabled the Africans and their descendants in those same circumstances not only to survive as an ethnic and cultural group, not only to retain a proud identify within the societies of North and South America and the Caribbean, but to create a culture which, through its music and dance, has gone out across the world, was not Christianity (the Indians were Christianized too) but the African ability to adapt and to tolerate contradiction, and, above all, the African assurance that the supreme value lies in the preservation of the community[;] without a community for support the individual is helpless, while with it he or she is invincible. (86)

I believe that Small is correct. Moreover, African philosophy has an aesthetic aspect which manifests itself in music, both the modes of making music as well as the meaning of music for the individual and for the community. And when we consider both the African philosophical framework which stresses adaptability and the evolved African American use of music as mother tongue, we can begin to understand why our music speaks to the world.

Consider the African essential: Given that humanity began in Africa, then to one degree or another, all humans have a common ancestry; we are all Africans. And whether we accept or deny this primal truth, Afro-centric music remains the most universally admired of all musics.

The conceit that music in general is a universal language is false. Chinese music, for example, has limited universal appeal. European classical music has broad appeal, but only in direct proportion to the dominance of European people worldwide. So how is it that African American music speaks to people worldwide when African Americans have no social dominance over anyone anywhere on the planet?

First of all, GBM retains not only the African pulse of life, a rhythmic sensibility/spirituality (the "drum connection") which all peoples relate to, but also, and more importantly, GBM retains the African principle of inclusion and adaptability. Essentially this means that there is room for everyone to be included on their own terms and that everyone can adapt the music to their own purposes.

Second, GBM expressly advocates freedom and democracy, individual expressiveness and collective participation. To a much higher degree than other musical forms which are often regimented and insist on the authentic reproduction of stylistic rules and modes, GBM stresses the authenticity of the musician and the audience as opposed to the authenticity of the musical form itself. Thus the artist is not only given the freedom to improvise, but the artist is encouraged to improvise (make a unique contribution). Until the music meets the needs of both the artist and the audience the music is not successful, no matter how faithful the performance might be to a specific musical form.

These two principles are unparalleled in any other musics of the world. Moreover, no other music had to carry as much aesthetic and social weight as did GBM. During slavery, Christian religious music was the only organized form of collective self-expression which both met our human needs and was acceptable to the dominant society. This is why religious music was the first genre of GBM to develop.

Gospel: Amazing Grace

In ante-bellum America the development of churches and the concomitant development of unique forms of musical worship by African Americans took place exclusively in the North. Reverend Richard Allen founded the African Methodist Episcopalian (A.M.E.) Church in Philadelphia in 1797, and in 1801 Rev. Allen compiled and produced a hymnal which contained original musical compositions as well as variations of traditional Christian praise songs. This music was closer to what became generically known as "Negro Spirituals" than to what we consider "Gospel"' music today.

In the South, where the overwhelming majority of our people were, the development of independent churches was not tolerated, and the compilation of hymnals was mostly by word of mouth. In the early 1800s a wave of religious revivalism swept across the South which was largely Protestant and independent of centralized church authority. In many cases, African Americans were included in the services, although segregated either in special sections of the camp meetings or at separate camp meetings. The accepted participation of enslaved Africans in American religious revival-ism is another factor in the rise of religious musical expression as the first form of GBM.

Up to the Civil War, there was a constant, albeit ever decreasing, influx of Africans into the overall Southern population. In the South, African modalities of cultural expression remained strong and obvious, while in the North, African cultural expressions remained strong but sublimated. Not until the post-WWI Great Migration, would religious expressions common to the South become the majority expressions of our people in the North.

The African religious modes of worship included trance and spirit possession, dance, communal chants and semi-sung oratory ("talk-singing"), improvised musical passages, and community sharing of hardships. Practices such as prayer services and the telling of one's determination gave each individual the opportunity to "speak" her or his piece as well as the opportunity to seek her or his peace in the Holy Spirit. While some African American Christians deny the relevance of such cultural practices and consider them either quaint or reprehensible expressions of illiterate people, these cultural expressions are philosophical projections of an African sensibility rather than a reflection of ignorance of European culture.

There is also a strong class bias to the sublimation of African aesthetical practices among our people. "Better off Negroes" do not go for whooping, hollering, shouting, and getting happy. In deference to acceptance of and by the Eurocentric mainstream, middle-class African Americans tend to sublimate their African aesthetics and appropriate Eurocentric modes of expression.

Prior to Emancipation, there was no overt mass development of an African American cultural presence distinct from mainstream Euro-American culture, precisely because a truly self-determined and fully expressive African cultural presence was politically unacceptable and constantly repressed at its every articulation. This began one of the major characteristics of African American culture: the masking of African elements within Euro-acceptable forms. For example, Afrocentric "processions" became Eurocentric "parades" (often with a martial character).

Generally, masking was not necessary for music because music neither created nor resulted in any concrete manifestation. To quote jazz artist Eric Dolphy, "After you play it, it's gone into the air." By contrast, the plastic arts (such as painting and sculpture), the literary arts, and other art forms (except dance) all have a concrete manifestation which called attention to itself.

Excepting those elements which were locked into a museum or warehouse as confiscated treasure, the European colonizer burned and destroyed every vestige of African culture. In America anything that "looked" African had to go, but Afrocentric culture existed and was constantly recreated in a "masked" form. Often such masked elements passed into the general body of American culture, and their African antecedents and essences went unrecognized. This is why most African Americans who are Christian do not realize that they have retained African liturgy.

Masking was often so successful that second- and third-generation African Americans could not decode the mask and thus began to identify the masked expression as non-African. In other words, we became unable to recognize our own contributions to the general culture because the contributions had been masked in order to escape repression, and the success of the masking made them unrecognizable as "African" even to succeeding generations of African diaspora people. This transformation and/or absorption (whether voluntary or by appropriation) into the dominant culture is one of the major dynamics of African American culture.

We often misunderstand the transformation of Africans into Americans and assert that it is solely a result of Eurocentric dominance. Our reality includes the intentional masking of African elements by African Americans in order to preserve those elements. The American reality also includes the masking of African elements by Whites in order to appropriate and/or commercialize the culture. This masked preservation/appropriation/commercialization dynamic is especially true of GBM, from the minstrel tradition, to Dixieland jazz, down to Madonna and Michael Jackson.

A key to understanding the complexity of masking and the propagation of African American culture is an appreciation of the constant transformation that the culture manifests as both a survival technique and as a result of interaction with external forces. In short, another defining aspect of African American culture is its fluidity.

So-called "Black culture" as a self-conscious and overt expression of our people did not exist until after the Civil War. The period of Reconstruction marks the actual formation of our four musical genres although, as I have acknowledged above, religious musical expressions predated emancipation.

The music that is considered classic "Negro Spirituals" was codified into a cultural force in the late 1800s when the spirituals were "spruced up" and presented as concert music in 1871 by the famous Fisk Jubilee Singers. Here begins the common practice of dating the development of African American music by its presentation to the Eurocentric mainstream and its acceptance by "Whites." Here also is the nexus of cultural production and cultural authenticity - i.e., until Afrocentric cultures are produced for (or more importantly by) Whites the culture goes unrecognized by the mainstream unless "money" can be made from controlling the sale of the cultural "product."

The commerce associated with the Black church, including the publishing and recording of Gospel music, has remained largely controlled by African Americans. Thus, it is no surprise that the history of modern Gospel music starts, in part, with musician/entrepreneur Thomas Dorsey and with Dorsey's immediate predecessor, the Rev. Charles A. Tindley, who composed and published what some critics consider the first modern Gospel songs. Tindley, who was at the height of his achievements as a composer between 1901 and 1906, marks the beginning of known individual composers of African American religious music. But whether you date the development of Gospel from the turn of the century with Rev. Tindley, or from the "Roaring '20s" with Thomas Dorsey, it was not until the 1920s that the music we know as "Gospel" was broadly practiced on a national level. The two best known exponents of this "new" music were vocalist Mahalia Jackson and composer Thomas Dorsey. It is instructive to note that initially Jackson, Dorsey, and others who practiced this new Gospel form were rejected and, in fact, prohibited from performing in some churches because they were accused of "jazzing up" religious music or of bringing "the Blues" (i.e., the "devil's music") into the church.

Mahalia Jackson was from New Orleans, the cradle of Jazz, and she subsequently went on to become recognized as the greatest Gospel singer of all time. Before becoming a devout Christian, and widely celebrated as the preeminent composer of modern Gospel music, Thomas Dorsey had been a Blues musician and performer who accompanied Ma Rainey and many other early Blues singers. Whether consciously or not, these artists were espousing the holistic African approach to culture which recognizes no inviolable separation of church and state.

In the 1990s, the "contemporary" Gospel movement, as exemplified by artists such as Bebe and Cece Winans, The Sounds of Blackness choir, and literally thousands of others, represent a continuance of the Jackson/Dorsey rejuvenation of Gospel to "include" the significant and essentially Afrocentric musical developments of the day into the religious music canon. Those who reject these artists today because they are making worldly music and calling it Gospel are of the same temperament as those who rejected such attempts in the '20s and '30s.

In the overall scheme of contemporary Gospel music, perhaps the single most significant development is the insertion of the drum. The drum, considered the "most savage and pagan" of all instruments, was indelibly associated with our African origins. The drum had always been excluded, indeed condemned, in Christian music making. That the drum today is found in the choir stands and on the stages of almost every Gospel concert is an amazing development that indicates not only the strength of African retentions but also the inevitability of Afro-centric cultural expressions surfacing among the masses of African Americans, even those who had consciously rejected the drum in previous times.

The drum, then, is a reaffirmation of Africanness rather than a contradiction of Christianity. But Gospel music does face a major contradiction - its movement toward commercialization. For African Americans, this contradiction, which can be encapsulated as the contradiction between performance and ritual in contemporary Gospel music, first appeared during slavery in Congo Square. Located on the then-outskirts of the city of New Orleans in what is now Louis Armstrong Park, Congo Square was a field on which enslaved Africans were allowed to dance and make music on weekends, and notably use instruments of their own creation and sing in African languages. Here is where the codification of African American culture first began, and here also is where the dichotomy between ritual and entertainment was crystallized.

For the gathered Africans this was ritual, a chance to establish community and articulate self-expression in keeping with an Afrocentric sensibility, but here also is where Euro-Americans came to observe and be entertained by Afrocentric music making. For the enslaved African and the native-born African American, dancing and singing in Congo Square were vital rituals, whereas for European and Euro-American observers, this was exotic entertainment (as well as unavoidably "erotic entertainment" - unavoidable because of the nature of race relations, the prevalence of miscegenation, and the French - initiated social system of placage, "octoroon balls," and other interracial arrangements between white males and women of color).

Congo Square existed from the 1700s up to the Civil War. But to this day there continues to be a Eurocentric audience for Afrocentric music, and this audience tends today, as it did then, to be a paying audience.

Gospel has retained much of its African character precisely because it is ritual rather than commercial. Indeed, except for a handful of professional recording artists, most Gospel artists seldom had to tailor their performance to commercial considerations. Moreover, the network of independent churches provided both a stage and a conservatory for the development of artists apart from the vicissitudes of popular trends. This is not to say that there are no trends in Gospel music. Certainly Gospel is subject to fads and the mass adoption of certain styles in a given era, but the adoption or rejection of commercial influences is not a life-and-death issue for Gospel artists.

The primary audience for Gospel music is an audience of "believers" who partake in the music making with the expectation of being moved to religious ecstasy. Through their collection offerings the Gospel audience (i.e., the church) supports the vocalists, choirs, instrumentalists, and musical directors. This audience validates the worth of the artist, not a recording executive, not the status on the commercial charts, not television (or radio) popularity, although all of these certainly play a role in contemporary Gospel music.

Completely apart from Eurocentric cultural concerns and apart from the pressure to sell to the mainstream, the church as a collective entity remains both a training ground for talent and a support center/validator of that talent as it develops. Additionally, each church has its own stars - Gospel artists who are revered within their own community. Currently, no other form of GBM has an African American base of support. Even Rap has a buying audience with a significantly large percentage of non-African Americans.

While there is no current danger that commercial concerns will dominate Gospel, there certainly is a danger that commercial concerns will become influential. Concerts can not replace the intimacy and authenticity of the church which functions year round, but commercialization unchecked can begin to erode the authority of the church as a cultural entity. On the other hand, the reaffirmation of Afro-centricity within the contemporary African American church means that there is a counterweight to any derogating effects of commercialism. Thus, a commercial group such as The Sounds of Blackness, produces a Gospel-based album which is overtly commercial but which is also suffused with overt Afrocentric concepts and musical styles.

The direction that the African American church goes will determine to a significant degree what direction the mass audience for GBM goes.

Blues: Laughing to Keep from Crying

Contrary to popular belief, the Blues is not slave music, even though slave-era work songs, field hollers, chants, and the like were some of the basic ingredients of the Blues. In fact, the archetypal image of the wandering Blues musician, roaming from town to town with his guitar, is de facto testimony that Blues musicians, as we know and mythicize them, could not have existed prior to Emancipation because our people did not enjoy freedom of movement during slavery.

The initial form of itinerant Blues music that became known as Country Blues is best exemplified by Mississippi's Robert Johnson. Johnson, who was born in 1911, was not the first to record nor was he the originator or even popularizer of the Blues or various Blues vocal and instrumental techniques; however, he was easily the most developed and forceful Blues musician of his era to record.

An accomplished guitarist and composer, as well as a mesmerizing vocalist, Johnson, who recorded only 29 songs during two different sessions in 1936-37, set standards for acoustic Country Blues performance which stand today. Literally thousands of performers, including many of the most popular and best known rock recording artists, have extensively "borrowed" Johnson's melodies, riffs, and even whole songs, often without crediting Johnson.(2)

A second form of Blues is known as the Classic Blues, the only modem genre of music which was led by women. In a country dominated by patriarchal values and male leadership (should we more accurately say "over-seership"?), Classic Blues is remarkable. Ma Rainey, Ethel Waters, Ida Cox, Alberta Hunter, Sippie Wallace, and the incomparable "Empress" of the Blues, Bessie Smith, were more than simple fronts for turn-of-the-century Blues Svengalies. These women often led their own bands, chose their own repertoire, wrote or co-wrote their own songs, and certainly composed or chose their own lyrics. Moreover, those who were truly successful, like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, actually ran their own production companies.

Never again have women performed leadership roles in the music industry, especially not African American women. The entertainment industry intentionally curtailed the trend of highly vocal, independent women - most of whom, it must be noted, were not svelte sex symbols comparable in either features or figure to White women, but robust, dark-skinned, African-featured women who thought of and carried themselves as the equals of any man. America fears the drum and psychologically fears the bearer of the first drum, the feminine heartbeat that we hear in the womb.

Without going too far out on a psychological limb, what is immediately clear is that the disappearance of big, Black women from the music industry had nothing to do with the tastes of or rejection by the African American record-buying and ticket-purchasing audience. I postulate that this disappearance had more to do with the inability of White males to deal with assertive (some would say "domineering") women. Outward resemblances notwithstanding, Bessie Smith was clearly nobody's Aunt Jemima.

Aesthetically, the music these women sang was closer to an amalgam of popular music infused with Blues elements than Country Blues per se. Indeed, it was only through a recording fluke that the Classic Blues first came to the attention of the general American public. When Russian-born immigrant Sophie Tucker was unable to make a recording date because of contractual conflicts, vaudeville and Blues musician Percy Bradford convinced Okeh, a small record label at that time, to allow one of his featured singers, Mamie Smith, to record. Eventually, they produced "Crazy Blues." The record was released in August of 1920, selling over 75,000 copies in the first month and over one million within a year. Soon the then-fledgling record industry was literally rushing to record every Blues-singing Smith woman they could find, thus beginning the industry trend of churning out clone after clone of what is perceived now as a "hit formula."

The third category of the Blues is the Urban Blues - the up-South, big-city variation of the Country Blues. Most of the founding fathers of Urban Blues were Mississippi-born transplants such as Muddy Waters, B. B. King, Howlin' Wolf, Willie Dixon, and literally hundreds of others.

These artists laid the foundation for modern pop music. As John Lee Hooker sings, "The blues had a baby / and they called it rock and roll." Except for the wholesale raiding of Robert Johnson's repertoire, there has been no larger cross-cultural appropriation than the coveting of Urban Blues songs by White pop artists - especially the Rolling Stones and the Beatles, two groups that, unlike their American predecessors and peers, actively acknowledged that they got their music from African American Blues artists.

Although White American artists such as Elvis Presley became rich copying "Hound Dog" from Big Mama Thornton and recording the songs of Otis Blackwell (an African American composer who would send Presley tapes so that he could learn to sing the songs), these artists did little to acknowledge and celebrate the sources of their riches.

In the 1990s, other than a handful of legendary figures, and a larger number of relatively unknown elderly practitioners, Whites dominate Blues - or, more correctly, they dominate the "representation" (as opposed to recreation) of the Blues. One central fact needs to be kept in mind: Other than the three schools of the Blues (Country, Classic, and Urban), there have been no real developments of the Blues as a form, although there have been significant transformations and off-shoots.

For example, the Kansas City Jump Jazz Shuffle (especially composer/arranger Jesse Stone and vocalist Joe Turner), mixed with the swampy syncopations of Southern Louisiana (especially producer, composer, and band-leader Dave Bartholomew and pianist/vocalist Fats Domino) produced the music we know as "Rock and Roll." Rock and Roll became really popular as an American artform when "Rockabilly" (White, Southern, Black-influenced country music) artists adopted the form. Key in this "masking" process was Sam Phillips, the owner of Sun Records, which recorded artists such as Jerry Lee Lewis and Roy Orbison. It was Sam Phillips who is credited with the prophetic statement, "If I could find a White man with the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars." Phillips found that man, Elvis Presley.

When Elvis burst on the popular music scene, the initial controversy was not about his singing but about his style of dancing - i.e., swinging his hips like a "coon." That's the point of the Elvis cameo in the Academy Award-winning movie Forest Gump, which glorifies America's innocence in the '50s.

This next statement is guaranteed to be controversial, but before you rush to get me a straitjacket, hear me out.

The Blues is dead!

One of the most vexing and seemingly contradictory aspects of GBM is that the majority of Blues fans, and arguably the majority of Blues musicians (no argument if you only count people 35 and under), are White. Why don't Black people listen to and play the Blues today?

There are all kinds of theories, but there is one simple fact: GBM is functional. Unlike Western culture, which is obsessed with eternal life, African culture accepts the inevitability of death and rebirth through generational transformation. Thus, when something dies, we grieve and then move on, carrying the spirit of the deceased within us as we create anew.

The Blues is no longer functional mainly because the conditions which created and sustained the Blues have changed. But the fact that the Blues, in the classic sense of a specific genre of music, is dead does not mean that we are not blue or that we don't have blues. It just means things ain't what they used to be.

Coming out of Reconstruction, we African Americans literally found ourselves emancipated but unliberated. The Union government reneged on its promise, and the South aristocracy let loose a viscous wave of repression designed to drive us back onto the plantation, only this time as wage slaves (a state akin to being serfs). Our serfdom was defined as "sharecropping," a system designed to keep us behind: behind the plow, behind the eight ball, always in debt, and never in control of our daily lives and destiny.

Many of us left the South. Literally walked out. In wise reaction to the Union's sellout, we decided to head west and thus added to the post-Civil War opening of the "Wild West" frontier - by some estimates, one out of every three cowboys was an African American. This story is fertile ground for further research, but my point is to focus on those who stayed South, especially in the Deep South areas where Jim Crow was most virulent. As Nina Simone presciently sang, "Everybody knows about Alabama, but Mississippi, Goddam."

In The Devil's Music: A History of the Blues, author Giles Oakley paints this despairing portrait of the Mississippi delta, the area most critics consider the oven within which the Blues was first baked:

By the 1890's there was a greater concentration of black people in Mississippi than in any other part of the country. In some areas blacks outnumbered whites by as many as two or three to one. This was especially true of the so-called Mississippi Delta . . . the local term loosely applied to that part of the State flanked on the West by the Mississippi River, roughly from Memphis to Vicksburg, and on the East by the Yazoo River. It is a flat plain, for centuries washed over by uncontrolled river floods accumulating some of the richest earth in the South. The land had been leveled and planted by slaves, who constituted a majority of the population as early as the 1840's. Levees were banked up to control the river flow and the area became more and more densely populated after the Civil War. As railroads and roads were developed, larger and larger numbers of poor and illiterate blacks were attracted to the area, drawn by promises of higher pay made by labour agents working for the white planters. Virtually limited to sharecropping and working on the new plantations owned by the whites, raising cotton to the exclusion of everything else, life in the Mississippi Delta was the essence of the black's segregated social isolation. The dominance of the white minority was absolute economically, educationally, politically and socially. Mississippi had a reputation for racism and bigotry from the earliest days of Emancipation; its record of lynching, reaching a bloody peak in the early days of the Jim Crow laws, was appalling. (46, 48)

Only by understanding the social context of post-Reconstruction Mississippi can we appreciate the origins of the Country Blues and the roots of the Urban Blues. Anybody who thinks African Americans are nostalgic about Jim Crow era America has to be ignorant or crazy, or both. In fact, we voted with our feet (first in terms of the Great Migration and then with Civil Rights demonstrations) to get out of the Jim Crow era, an era which was the crucible for the production of the Blues.

The Blues is dead because the soil that produces the Blues either lies fallow or has been covered with concrete. However, the Blues sensibility, the impulse to rise above by declaiming just how tough times are, the laughing to keep from crying, the celebration of the transformatory power of violence - all of that is found in the Blues music of the '90s, which is, of course, Rap.

We as a people have never been hung up on perpetuating the American status quo. Our goal has always been to either flee Babylon or burn it down, to leave it or change it. In the case of the Blues, as a specific reflection of Jim Crow America, we did both - we left the Blues as a specific genre of music and we transformed the Blues into other popular forms of music. In fact, what is Rhythm and Blues but post-WWII Blues, and what is Rap but a literal recitation of the Blues over "phat rhythms"?

What we must distinguish is the difference between process and product, between focusing on a sensibility which informs the creative process and the forms which are the result of a specific creation. The Blues as a historic genre is dead. The Blues as a sensibility is very much alive. The Blues is dead. Long live the Blues!

Jazz: I Got The Heebee Jeebies

Of all the forms of GBM, Jazz is both the most misunderstood and the most powerful as an influential social and musical phenomenon. The origin of the word Jazz as applied to the music is shrouded in myth and anonymity. It is known that "jazz" had a connotation of sexual activity. How or why this term was used to describe the music, however, is not known.

One of the most common and inaccurate myths about Jazz is that it was born in the brothels of Storyville in turn-of-the century New Orleans. The truth is that Jazz was born in the streets and parks o f the New Orleans African American community. Initially, Jazz was primarily an outdoor music performed at social occasions such as wedding receptions, funerals, parties, births, parades, and picnics.

The man credited with being the founding father of Jazz is trumpeter Charles "Buddy" Bolden, who merged the popular music of the era (especially Ragtime) with the Blues. (Note that many of the early Jazz musicians also recorded as accompanists to Classic Blues performers - e.g., Louis Armstrong backing Bessie Smith.) This merger was a brilliant stroke of African genius. Once again, the African aesthetic of inclusion and infusion worked to produce a synthesis, Jazz, that was greater than the sum of its parts.

Another misunderstood aspect of Jazz is that it is exclusively or mainly a solo improviser's art. While there is no doubt that improvisation is a major hallmark of Jazz, improvisation is not unique to Jazz, and Jazz has a major history of composition dating back to its beginnings. Indeed, the "other" founding father of Jazz is Ferdinand "Jelly Roll" Morton, a contemporary of Buddy Bolden's, who was the first major Jazz composer and arranger.

In the context of world musical culture, Jazz is the only serious alternative to classical music as a major musical art form. Although, in relation to European classical music, Jazz is relatively young, Jazz (along with the other three genres of GBM) has exerted more dominance on world perceptions and practices of music than any other musical form. Moreover, in the later half of the 20th century, GBM has superseded classical music in informing, influencing, and, in some cases, dominating world musical tastes and practices. This is especially true if one focuses on the recording and documentation of music, and on the creations and comments of musicians. And given that the last five hundred years have been an era of European world dominance, this is an especially striking development. Part of the explanation is that Jazz specifically, and GBM in general, flew around the world on the back of the American eagle, often masked and presented as "American" music in white-face.

There is, of course, an element of truth to Jazz being the "Whitest" form of GBM. From its early days, Jazz has always had White practitioners. Moreover, the first major commercializer of jazz, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band (ODJB), was an all-White group led by cornetist Nick La Rocca. In 1917 the ODJB opened at Reisenweber's Cafe in New York. In February of that same year, on Victor Records, they cut the first Jazz record and kicked off the national musical love affair that would later be dubbed the "Jazz Age." Although the reality is that no major Jazz musician copied either the band's style or LaRocca's style, the ODJB is sometimes cited as critical to the development of Jazz by those who are intent on citing the existence of non-African American practitioners as proof that Jazz was significantly developed by White musicians. Indeed, from 1917 on, there has been a continuous racial boosterism of specific Whites as the dominant forces in Jazz. ODJB was quickly followed by Paul Whiteman, Benny Goodman, Dave Brubeck, and so on. Of course, this industry-induced racialism did not necessarily reflect the personal attitudes and actions of those Whites who were lionized by the media. Just as the fact that Blacks singing opera doesn't negate the fact that classical opera is a European art-form, the existence of White practitioners in no way means that Jazz is not an African American artform.

Another misconception about Jazz is that it is essentially African rhythms, European harmonies, and American melodies. I think that's one-third correct - there is no doubt that Jazz utilizes American melodies (and, for that matter, any other melodies that Jazz musicians find attractive). The fact of the matter is that Jazz is born out of the American matrix and was kreole from the "get go." But this musical kreolism is not an equal mixture of racial elements; rather, it is an adaptation of various cultural elements via an Afrocentric sensibility.

Jazz rhythms use straight 4/4 time, which ca n not be said to be African; but how the 4/4 is used - i.e., "swinging" - is African American. Jazz is both a specific: creation of African Americans anti a general reflection of the Afrocentric perspective of its creators.

As for harmony, clearly the harmonic substructure of Jazz is the Blues, which is a "good, long ways" from standard European harmony. The basic harmony of Jazz maybe European, but what distinguishes Jazz is its Blues tonality.

Blues and Swing are the two major structural foci of Jazz. To the degree that one plays Jazz that neither swings nor employs a Blues tonality and/or sensibility, one is playing a form of Jazz that is not very "Jazz-like." The genius of the music is that it is possible to play authentic Jazz and at the same time be far removed from the central focus of the music. It is possible, for example, to play Jazz in a Eurocentric manner - i.e., to emphasize product and technique over process and emotive prowess.(3)

The central point to understand about Jazz, especially in the contemporary context, is that Jazz has a dual tradition that sometimes may seem to be contradictory. Buddy Bolden represents the Bluesy popular element and Jelly Roll Morton (who was fond of loudly declaiming that he invented Jazz) represents the compositional, formalized element. Wynton Marsalis is the Jelly Roll Morton of this era.

Those who dismiss Marsalis's "neoconservatism" make the mistake of focusing solely on one aspect of Jazz and ignoring the other. Wynton and Jelly not only share New Orleans as a birthplace, they have similar temperaments, and congruent emphasis on playing the music correctly. Moreover, as time goes on, Wynton Marsalis is focusing his energies on composing music. His major hero is Duke Ellington. The real deal is that Wynton Marsalis has a concrete/sequential personality and a high appreciation for technical and structural integrity. Because he has a bent toward repertory, toward "classical" study, he is attempting to preserve the best of previous eras.

The rub, of course, is that technically replicating the past is not the same thing as extending the tradition. Indeed, when Jelly Roll, Duke, Monk, and countless others were creating what we now consider classic music, they were challenging the then-status quo, shattering the old molds and creating completely new forms of music. They were also playing the truths of their contemporary life experiences and not trying to repeat what had been done by the generation before them.

The major problem with much of the Jazz in the '90s is that many young musicians are so intent on recreating old forms that they have nothing new to say. And a major part of their silence evolves from the fact that they are the products of an uneventful assimilation into the American status quo: Their music has no fire because there is no fire in their personal lives. And, as Bird said, what comes out of your horn is your life.

In the '20s, Jazz musicians traveled around the world and through the entertainment underbelly of America. They were the most internationalist-minded and, at the same time, nationally repressed of all artists - lionized abroad and denigrated at home. Many lacked formal education, but they had lives that necessarily included fighting for their rights as human beings and artists.

Today's young Jazz musicians have college degrees in music (often in Jazz Studies). When they tour, they have hotel rooms, limousines, recording contracts with riders calling for fresh fruit, juice, select wines, or liquors, specific sound equipment, and so forth. I am not advocating a return to hard times, but I am pointing out that the fire of Jazz must come from the musicians. If the musicians are enjoying (as they should) relatively comfortable careers, then the fire has to come from some place else in their lives.

Historically, poorly paid Jazz musicians have been the epitome of "starving artists." They persued their art despite economic injustices and inequities, not because they wanted to starve but because making money was not the main reason for creating Jazz. Jazz was their religion, rather than simply their career.

Jazz in the '90s has become a middle-class, respectable pursuit. So is it any wonder that much of today's Jazz does not relate to the lives of the working class, under- and miseducated, poor and de facto segregated urban masses of African Americans?

If Jazz has a future it will only be in the sphere of international (or what some people would call "multi-cultural") cooperation and collaboration to contest the aesthetic, political, and economic domination of post-colonial capitalism (regardless of the color of the capitalist). When will the people who create the music control the production, distribution, and consumption of the music? Traditionally, the Jazz musician has been at the forefront of asking this question, of fighting for self-determination and self-respect. It remains to be seen whether that continues to be the case.

Black Pop: Dance to the Music

My basic contention is that if our popular music is in sad shape - and in general Black popular music is abysmal - then we as a people are in sad shape. What we are witnessing (and too often participating in and collaborating with) is the total commercialization of our music. Thus, R&B (whether Disco, Funk, or New Jack Swing) and Rap are both designed mainly not only to sell records but also to sell to an audience which, to a significantly large degree, is not Black. If this audience were the large majority of people in the world who are the descendants of the colonized, this would be a good development. However, the "auditors" of fame and fortune in America are largely White: White youth in revolt against their parents, a White music industry in capitalist profiteering of the sale of the music, and a White-controlled media which exists as an adjunct (and advocate) of the business sector.

The integration of African American artists into the mainstream of the entertainment media necessarily results in a dilution and/or prostitution of the music. Rather than present the history of Black Pop/R&B, I will focus on the latest development: Rap.

The Words and the Beat - That Is the Music. While some adults still argue about whether Rap is really music, Rap has become a major force in American popular music. Although Rap certainly does not sound like Eurocentric music, Rap is still music, albeit rhythm-based rather than melody- or harmony-based.