I KNOW YOU MARDI GRAS

A signification of recognition

of our aspirations and our social reality

Clyde R. Taylor is a sage—a wise and intelligent teacher; wise in that he knows what to do with all the information that he knows, intelligent in that he has, and utilizes, an astounding amount of information.

Clyde R. Taylor is a sage—a wise and intelligent teacher; wise in that he knows what to do with all the information that he knows, intelligent in that he has, and utilizes, an astounding amount of information.

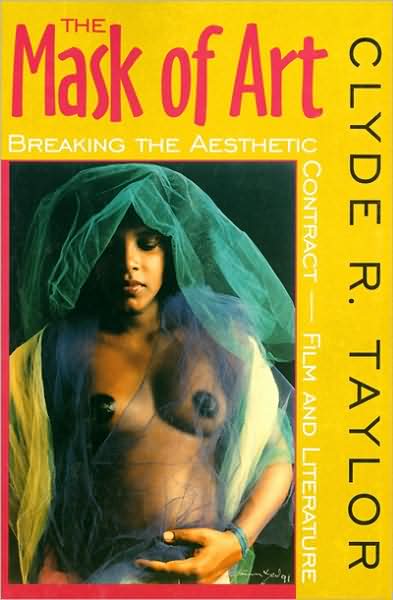

A five minute conversation with Clyde is enough to convince me, and anyone else of average education, that we really don’t know much of anything about, well, about anything. The work that Clyde self-depreciating simply calls a book, i.e. The Mask Of Art, is de facto proof of our ignorance. Clyde’s range of references is so vast that how much I don’t know became clear to me by page nine or ten. Were it not for Google, Wikipedia and other quickly available online resources, in order to read and fully digest chapter one alone would probably require my sitting in a major library for two or three weeks.

I don’t know about you but I am certain that Clyde is a miracle in terms of studying and understanding the thought and behavior of our historic oppressors.

Let us be clear. Let us recognize the aroma of gunpowder, of conquest that whiffs and wafts through the halls of the academy—the academy is the intellectual superstructure, the intellectual citadel atop the hill. The main task of the academy, a task that the academy does exceedingly well, is, at the very least, to humanize oppression and at its very best is to glorify the oppressor. Period.

Reductively, the art that academy valorizes is the mask on the horrors of conquest.

I am a street level, organic intellectual. I did not learn what I know in any academy. The academic term for me is autodidact—I taught myself. Actually, that is not the case, it is just that the academy holds little if any recognition for the wisdom of the people who have taught me.

In the brief moments I have, I should like to offer a few observations, all of which have been sparked by conversations with Clyde Taylor and by reading and reflecting on his book, The Mask Of Art.

I will address three of the many concerns that Clyde has been instrumental in instigating.

1. Masking and my three categories of masking.

2. The deep “what does it mean to be human” focus of aesthetics.

3. The broad question of cultural critique within the context of oppression.

Perhaps, “address” is too specific a term for what follows, perhaps I should say I would like to mention three of the many concerns that Clyde has been instrumental in instigating. Adequately addressing any one of these concerns would require a rather dense book. I do not mean to present myself as a savant sharing a worldview, when it would be more accurate to say I am merely a fool asking a few questions.

ONE—MASKING.

The common conception is that the mask conceals but I believe the mask also reveals. The mask reveals the intentions and desires of the mask maker and the mask wearer. The mask also inherently raises the question of why? Why wear the mask? Is the mask a cover for feelings of individual or social inadequacy? Or, is the mask actually a recognition of individual or social inadequacy?

Of course the mask comes in numerous forms, too numerous to cover here, but I ask you to consider your clothing. My dashiki, your suit and tie, the color eyeglasses I wear, the color and style of shoes you have on. Clothing is the elemental mask we wear.

Clothing cloaks our physical vulnerability and enables us to, as the Europeans say, “withstand the elements.” In the Western urban world, clothing also signifies. It signals social status (or social aspirations) and many other concerns.

I do not need to go into the obvious. I think you understand that grooming is a mask: lipstick, deodorant, perfume, etcetera, etcetera. Any physical thing or social concept we attach to ourselves to distinguish ourselves, not only from our fellow humans but also, and more importantly, distinguish ourselves from who we are without whatever we have donned, any and all of that is a mask.

One of my students responding to questions of defining humanity during a discussion of the Epic of Gilgamesh compared and contrasted to the Epic of Bewoulf, offered the observation that being human is partly defined by being mobile, i.e. physical movement as a group or individual across the face of the planet. Implicit in that observation is a critique of the modes of mobility.

Think for a minute about the mask of mobility, how we choose to “get around” and what that choice says about us.

I’m sure some of you recognized that my use of the term “get around” implied far more than mere physical mobility. My usage also implied social mobility with a specific subtext of socio-sexual mobility. Yes, I mean to imply some of us wear the mask to bed, indeed, in a social sense, some of us never go to bed without wearing a mask.

So then the very process of masking, of concealing, is simultaneously a process of revealing; a process that reveals essential characteristics of the person who dons the mask, characteristics whose origins are often situated in desires that drive if not outright determine behavior, as well as characteristics and/or feelings of shame or inadequacy.

One function of the mask is to conceal, and in fulfilling that function the mask reveals.

When we wear the mask are we the same as we were before we put on the mask? Does a mask fundamentally change us or merely change the viewer’s perception of the wearer?

Speaking from the perspective of African-heritage cultures in general and New Orleans in particular, I believe that the mask can have transformatory powers, even if that transformation is solely a new surface identity for the wearer.

In New Orleans one traditional saying upon encountering a masked person whom one recognized beneath the mask is: “I know you Mardi Gras.” But the saying also has come to mean I recognize that you are masking, that you are celebrating, that you are transforming yourself. In that context the saying has application outside of the specific’s of Fat Tuesday traditions.

If you talk to the Mardi Gras Indians they will tell you, when they mask Indian, they become something else. Masking can be a conscious effort to transform the self, to contact the spirit world, to serve as a vessel for outside forces to manifest themselves. Masking can then transform the self, transform the wearer both physically and psychically.

Some of us know the transforming process as trance. Another example would be catching the spirit in church but there, it is interesting that the transformation is possible without the physical mask, even as the more perceptive cultural critics recognize that the church service is itself a mask to conceal the trance process. Christian liturgy was acceptable to the slave master, African religion was forbidden. Enslaved Africans masked the persistence of African religious practices in the outward dress, i.e. the mask, of conformity to Christian liturgy.

Masking also enables a transformation of perception, i.e. the viewer no longer sees the wearer but rather sees what the wearer is wearing and makes assumptions about the wearer based on that perception even as the viewer is partially (or fully) aware that they are looking at a person wearing a mask.

Obviously this discussion of masking and transformation could go on for centuries but we will stop here to go to the third element of masking.

Masking is an aesthetic statement, what we consider good and beautiful. In New Orleans on Mardi Gras day when the Indians come out, the perennial question is: who’s the prettiest? This emphasis on aesthetics is recent in the tradition and is attributed to one specific person: Big Chief Allison Tootie Montana.

Before Tootie, the Black Mardi Gras Indian gangs used to literally fight each other. After Tootie instead of the knife, hatchet or gun, the fighting was done with needle and thread, beadwork and feathers.

What a sight to see two chiefs meet and engage in an aesthetic battle: who is the prettiest, whose plumage the most colorful, whose design the most intricate, whose suit told the strongest story, etcetera, etcetera.

Although I have used the example of Mardi Gras Indians, obviously it applies to any and all forms of masking. The mask can be a positive statement of ideals or a negative statement of condemnation. Through the use of the mask the wearer can say this is beautiful or conversely this is ugly, for after all aesthetic statements are judgments.

The mask conceals/reveals, the mask transforms (not only the perception of the viewer but also the social, and sometimes even the physical, manifestation of the wearer), and the mask makes an aesthetic statement.

TWO—WHAT MAKES US HUMAN?

Ultimately the mask of art is a way of addressing the question at the core of human systems of thought: who am I, which reductively is the question of what does it mean to be human?

Throughout his book, Clyde Taylor prefaces the names of references with racial/cultural designations. Clyde will append “white” such and such to a person’s name. The tag is used as identifier. Only an outsider would think of using such a tag and in so doing identifying the limits of the person, object, or construct so tagged.

This begs the stunning question: are white people humans? Of course that is a reversal of the usual use of the racial designation. For centuries whites have explicitly or implicitly asked that question about people of color. Similarly, for centuries some of us whom whites have designated as outsiders to humanity have been asking the critical question about Europeans, are they human?

For a very specific investigation of this question read Jewish authors such as Primo Levi discussing Nazis who imprisoned and attempted to exterminate the Jews. Levi also asks the question: did the concentration camp dehumanize its victims.

If we restrict our investigation to Black and White we have unwittingly bought into the paradigm that our oppressor established. There are of course many other ways to approach this question of what makes us human human and the question of whether a sociologically, or racially, or politically defined group of people are humans.

By the way, I believe that the Middle East quandary is an example of forcing a European problem on non-Europeans to provide an answer. The national institutionalization of anti-Jewish, genocidal behavior happened in Europe, not in the Middle East. Why was not a piece of Germany or Austria carved out for the Jewish homeland?

Returning again to our study of The Epic of Gilgamesh compared and contrasted with the Epic of Bewoulf, we asked the question: is conquest and war intrinsic to human existence? We also asked our students to discuss the role of women in humanizing men.

One of my students noted in following up on the idea that it was women who humanized men, observed that men needed to be humanized while women were born human. During class discussion we formulated the theory that to be human is to become woman-like.

That’s an interesting discussion in light of the biological fact that all fetuses start off as females and that it is the introduction of the testosterone that facilitates the mutation of the fetus from female to male. Or, put another way, the basic, the elemental human condition is female. The art of Gilgamesh provides us a focal point to discuss the essence of being human.

The role of art is, or ought to be, an expression of our humanity, as complex and contradictory as our humanity is. Some of us believe in the maxim: cogito ergo sum. But does thinking prove being and is “being,” i.e. existence, ipso facto the central question for humanity?

Here is where art goes far beyond thought. One of the reasons I admire Clyde Taylor’s book is because he constantly probes at the question of what it means to be human.

Although I recognize that in the 21st century it is inevitable that we will focus on European thought simply because our discussion mostly takes places within academe and we mostly utilize European languages for the discussion. While it is easy to recognize the role of European conquest, hence the color dynamic inherent in the use of European thought as the predominant reference for aesthetic discussion, there are not only other systems of thought outside of Europe, there is also a significant other discussion within Europe.

At the risk of shorting out the discussion by moving too quickly, let me simply say: not only was there a world of humanity before European world conquest, but indeed there was also a world before patriarchal conquest. Moreover, those pre-existing worlds, are far, far older and existed far, far longer than the current European era of dominance.

We reference Europe because we have been dominated by Europe but if we look at the history of humanity, we understand that human history stretches for tens of thousands of years prior to our current state of conflict and confusion.

To put it even more succinctly, the first gods that humans recognized were women of color. Women were our gods of antiquity. The revolt of men to erase that recognition and to impose male domination on women is the essential element of civilization as we know it.

In academic terms: to be human means to dominate women. The reason I say academic terms is because the academy situates itself in the written word. The development of the written word within civilization is congruent with and, as some of us would argue, a manifestation of the male dominance of the female.

Hence we privilege text in our discussion of humanity, especially when we discuss the universality of aesthetic concerns, a universality won and enforced by men with guns. Indeed, a succinct description of western civilization could be summed up in three words: men with guns.

From “men with guns” there is but one short step to the academy, i.e. men with books!

The irony of Clyde Taylor’s book, The Mask Of Art, is that the cover situates the female figure, or image, as the focus but the majority of the text actually focuses on the thoughts of males. Part of the reason for this is that the majority of texts have been authored by males. Taylor does not shy away from recognizing this limitation and redeems his text by privileging the critique and insights of Sylvia Wynter in the concluding chapter.

Additionally, in chapter 13, “Daughters of the Terreiros,” using a critique of Julie Dash’s film, Daughters of the Dust, Clyde Taylor identifies the importance of women “within” the discussion. On the last page of the chapter, Taylor also gives us a reading of the cover image.

My concern is that both the critique and the explanation of the cover are situated within the boundaries of civilized discourse, hence within the framework of male dominance. The female remains an object of male discourse, an object gazed upon by the male whose signification is explained not by her own words but by the interpretation of a male.

I am saying men with books is a problem whenever that formulation restricts the agency of women. To be clear, I am not arguing for the rise of women with books. My critique does not simply call for a change of author, i.e. I am not simply advocating women with books, nor am I simply advocating both women and men authoring books. I am also critiquing the use of the book as the defining object of civilization.

As long as the discussion is limited to text, the “other” (i.e. those whose origin is outside of Western civilization) is doubly at a disadvantage. One, we are disadvantaged because many of our strengths, particularly in the areas of music and kinetics, i.e. dance and procession, are excluded from the discussion. But, two we are disadvantaged because a major part of the problem is not that we don’t write books (whether the absent author be people of color, or be women, or both). The problem is that the very construct of text, as we know, is a problem, especially when text is established as the arbiter and authority on what it means to be human.

For those who are interested in “reading a text” which discusses this “text” dilemma, I refer you to The Alphabet Versus The Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image by Leonard Shlain. Some of us believe we are living through a major transition, moving from text to image as the site of authorial social expression.

It seems significant to me that the chapter that focuses on a woman author is about a film and not a book. Of course, this has been one of Clyde Taylor’s abiding and essential strengths, as erudite as he is, he is comfortable, perhaps even “more” comfortable, in discussing the image as he is in explicating text. Clyde Taylor’s facility in critiquing both text and film is critical to my appreciation of his importance as a cultural critic.

3.—RETURN TO THE SOURCE

Finally, I think it important to acknowledge Clyde Taylor’s recognition that he is a spy behind enemy lines. The academy is not his home. His workplace is not his hearth. The contested and often conflicting dichotomy between home and work is a hallmark of modern society, a contradiction that has yet to be resolved.

Productive labor is one of the essentials of human activity. If there is a contradiction between where and how we earn our living, i.e. the workplace, and where and how we express and propagate our humanity, i.e. the home space, then, unavoidably, we find ourselves in a situation of anxiety and alienation. This anxiety and alienation is another hallmark of modern civilization, especially given that today there is very little, if any, overlap between the community of the workplace and the community of the home.

This alienation is particularly sharp for the outsider to the workplace whose success at fitting in at work creates a persona that is both alien to and uncomfortable within the home space, and vice versa. This workplace alienation is intensified if the workplace is academe. Working in the big house is strange enough but to be an intellectual personal “manservant” is particularly off-putting. Moreover, I fully recognize, as Condi Rice exemplifies, women can also be manservants.

In this regard, Amilcar Cabral’s famous dictum, “return to the source,” is of particular relevance. If, for whatever reasons, we can not return to our source, invariably we will establish a surrogate home in a space that is either not congruent with our original home or which is shallow in comparison to the social depth of our original home.

Alcoholism, and other forms of addiction, are major liabilities of a career in the academy. One must take something to deaden the pain of anxiety and alienation; the best, although far from easiest, prescription is return to the source.

While I often joke with my students: remember, we are sending you to college to bring back the fire, don’t stay and become fascinated with the light show, I recognize, however, and Clyde Taylor’s book reinforces, that in returning to the source we must go beyond the boundaries: both the boundaries of dominant civilization but also beyond the boundaries of our source.

Clyde Taylor and Amilcar Cabral realize that unless and until we are able to move through the world learning from and exchanging with all peoples inhabiting the planet without complexes of either inferiority or superiority, until such time we are not truly free.

Thank you for your attention and consideration of these brief remarks.

—kalamu ya salaam